Avoid planning delays

Nottingham City Council applies a thorough design review process to secure design quality and sustainability. The level of information Nottingham requires at planning stage is often misunderstood and underestimated by applicants. However, engaging in early conversations and having an attitude of collaboration and trust, can save applicants significant amount of time.

A. Engage in pre-app

Applicants are strongly advised to engage in a Pre-application process (pre-app).

For large schemes, Nottingham City research showed that, from point of first contact to permission being granted:

Schemes that engaged in pre-app were an average of 10 weeks faster than those that did not engage.

Schemes that engaged in pre-app had an average of 11 fewer planning conditions than those that did not engage.

B. Provide the requested information

The lack of appropriate information is a typical cause of delays and inefficient use of local authority resources.

Applicants often submit pre-app and planning packages without a good site analysis. This is the most common cause of delays and unsuitable responses to site conditions. Nottingham expects to see a site analysis with identified constraints and opportunities and an description of how designers arrived to their proposals prior to a concept design being established.

It is common to see proposals drawn in isolation (e.g. site plans and elevations), this will inevitably slow the process down, as officers need to evaluate the impact of the scheme in its setting, which is impossible to do without the contextual information. Always show elevations and adjacent/street façades (e.g. using aerial images, photos and/or streetscapes to show what’s adjacent to the scheme.

Detailed sections and plans, as well as material specifications (e.g. durability, installation system, colour specification in RAL) are often requested at pre-app. Having a good understanding of how the scheme will materialise is crucial to the speed of the planning process and the number of planning conditions applied.

C. Be prepared to collaborate

At Nottingham (a unitary authority), we review schemes from a range of perspectives as a team (highways, drainage, urban design, planning, heritage, etc.), we have been able to evidence that this collaborative process is crucial to speed up planning processes and so we have preference to work in collaboration (often co-design) with applicants in order to save time and resources.

It is often the case with some applicants (a minority), that they show a reluctance to work in collaboration across sectors, which tends to cause huge delays.

Applicants might be invited to multidisciplinary design reviews and/or design workshops to discuss solutions that work for all and to take proposals to an acceptable standard.

At times, applicants will receive comments from officers but afterwards, they would re-submit the scheme without amendments, not having addressed the issues highlighted. It is crucial that, if designers cannot find a solution to an issue, they contact the urban design team seeking for help as soon as possible to avoid further delays.

D. Get the design right

Typical causes of planning delays for LARGE SCHEMES are:

Street hierarchy: a clear street hierarchy is fundamental. Schemes that do not demonstrate clearly how criteria 2.2.1 of the New Streets Design Guide is achieved will suffer delays at planning stage.

Innovation: designers are welcomed to suggest alternative innovative solutions as long as these comply with Manual for Streets but should be aware that the planning process might take longer, as different departments need to be consulted to ensure proposals are practical and viable in the long term.

Incorporating trees: Nottingham City expects to see tree-lined avenues and a substantial amount of new trees in medium and large residential schemes. However, good, significant specimens that reach their full growing potential, located in strategic point to aid placemaking, are always a better option than many insignificant, small tees scattered randomly across the site (also see 3 below).

Parking balance: parking distribution is a crucial consideration and the City Council will expect a good, balanced distribution of parking modalities as per criteria 2.5.1 of the New Streets Design Guide.

Car dominance: curtilage parking with more than six cars in a row is non-compliant with criteria 2.6.1 of the Housing Design Guide. Non compliance is very likely to result in delays at planning stage.

Gaps: wide spaces between properties to accommodate more than one parking space on-plot is non compliant with criteria 2.1.2 of the Housing Design Guide and will not be considered acceptable.

Boundary treatment: proposals are expected to eliminate all undefined strips of land, for example around dwellings/adjacent to footpaths. Land should be either fully allocated to private ownership or under adoption by an authority (Highways or Parks and Open Spaces). Land falling onto management company must be clearly demarcated and in single large zones forming recreation or green assets, rather than in small strips.

Avoid Highways delays

What causes highways delays?

In recent years, our industry found Highways to be one of the main reasons for delay in housing delivery. Overengineered movement infrastructures and car-led design has resulted in poor design quality environments that discourage pedestrian and cycling movement in favour of private vehicle use. However, Nottingham City, as a unitary authority, has been ahead of the kerb in pushing for innovation and people-led street design. Working towards the Manual for Streets standards since its first publication, Nottingham has just updated the New Street Design Criteria that will sit within the Area Wide City Code and which includes technical standards for streets and parking (links below). The vision for Nottingham is to deliver:

“…streets as PLACES, ecologies we share with other species. Vehicles happen to be able to circulate through these ecologies.”

“…a people-first design ethos and therefore, streets that are not designed primarily with vehicles in mind.”

“…the inclusion of cycling lanes and sustainable drainage measures from early stages in the design concept.”

But despite the guidance, criteria and technical information being offered to applicants, the authority remains battling for design quality daily, engaging in design workshops, co-design sessions and often having to re-design schemes on behalf of applicants to achieve a minimum design quality threshold and crucially, to provide a sound, future-proof infrastructure. In this article, we show the process we engaged in on three occasions and how schemes changed from the initial sketch to the granted scheme.

NOTTINGHAM CITY HIGHWAYS DELAYS AUDIT 2018-2023

There were strong trends and consistencies across all cases in the way different developers approached the design stages and in how they responded through the planning process. Although assistance - and often training - were offered to all applicants during pre-application stages, in some cases it took a long time to accept design support from the authority. Despite the design issues highlighted being so fundamental, housebuilders believed they knew their business and how to make things work. Unfortunately, in most cases, they demonstrated they knew how to deliver their standard models and how to achieve their margins, but they failed to design good placemaking and coherent neighbourhoods that could sustain resilient communities.

Lack of skills on the following topics

Highways design and placemaking principles.

Site complexities, including levels, flooding, contamination, microclimates, geography, context, etc.

Levels implications on how the place functions and how it is perceived. Working on plan (not 3D) without consideration of heights and how places are perceived by humans.

Vehicular access and movement first approach: this is what we call car-led design, streets being the first consideration in giving structure to developments on the basis of vehicular movement. The correct approach is the Street Ecology ethos.

Technical details and how these can have major implications on place quality.

Poor attitudes found through the process

Disinterest and unwillingness to address issues raised by the authority. Instead, a predisposition to push proposals through in their initial form or with insignificant changes.

Design processes being driven by housing finance teams, who often disregard their internal design teams’ recommendations.

Predisposition to overlook ecosystems, biodiversity and water management and assumption to add these at a later stage.

Tendency to leave landscape design as a later add-on, rather than incorporating features and trees as an integral part of the design.

Tendency to resolve planning issues at speed but with minimal or no design changes. Planning was be perceived as a burden rather than as an opportunity to achieve better places.

Disregard for how residents would interact, socialise and enjoy their new neighbourhoods. Instead, a tendency to view houses as places where people drive to and neighbourhoods as sanitised, transient groups of houses.

HOW TO ADREESS THE ISSUE

For decades, the planning process has continued to absorb the responsibility to safeguard design quality. This has brought along a fear of change, a reluctance to pilot new models, a platform where developers and authorities are delivering poor design by “failing without trying”.

A plethora of tools have been introduced over the last few decades, from Design and Access Statements to Design Guides, from Design Review Panels to Design Code. All useful and with a role to play, but all trying to put a plaster over a major wound. If housing delivery is such a priority, then why, as a nation, we are not investing in adequate higher education courses and apprenticeships to address the main barrier to delivery: appropriate housing and neighbourhood design skills?

Six Trending Highways Design Issues

Design issues on planning submissions cause serious delays on a regular basis, and they cost authorities across the country significant time and resources. In Nottingham, we found highways design issues that are easily avoidable, are also recurrent. We show some examples below.

1. Road Hierarchy and Radii

Proposals tend to include street networks without clear hierarchies. Road carriageway widths tend to be 6-8 metres, with all corners in a 6 metres radii. But not all streets need to be that wide. Nottingham Street Classification Guide shows carriageways varying from 6.5m to 3.6m.

2. Traffic Calming

A trend has developed over time to include wavy and gently curved roads as an attempt to soften the impact of the car across the landscape and to reduce vehicular speeds in residential areas. However, this is a highly inefficient way to design road infrastructure, one that consumes huge amounts of land, the biggest commodity in housing delivery. Road curvature does not reduce speed when carriageways and radii are wide and pose no physical obstacles to vehicles.

3. Cul-de-sacs

The use of dead ends has become a popular way to deliver quiet zones within residential areas. Unfortunately, this is an inefficient urban pattern that consumes large amounts of land. On the other hand, dead ends discourage walking and cycling, instead, they prompt further individual vehicle use. There are some benefits with dead ends (like policing), but research shows the negative consequences of cul-de-sac layouts outweigh the positives.

4. Turning Heads

Another consequence of dead ends is the need to accommodate large turning heads to cater for waste collection, service and emergency vehicles. Large turning heads not only take up land, but also contribute to making environments less welcoming to pedestrians. Alternative design solutions are not explored enough, instead, the traditional oversized model remains favoured.

5. On Plot Parking

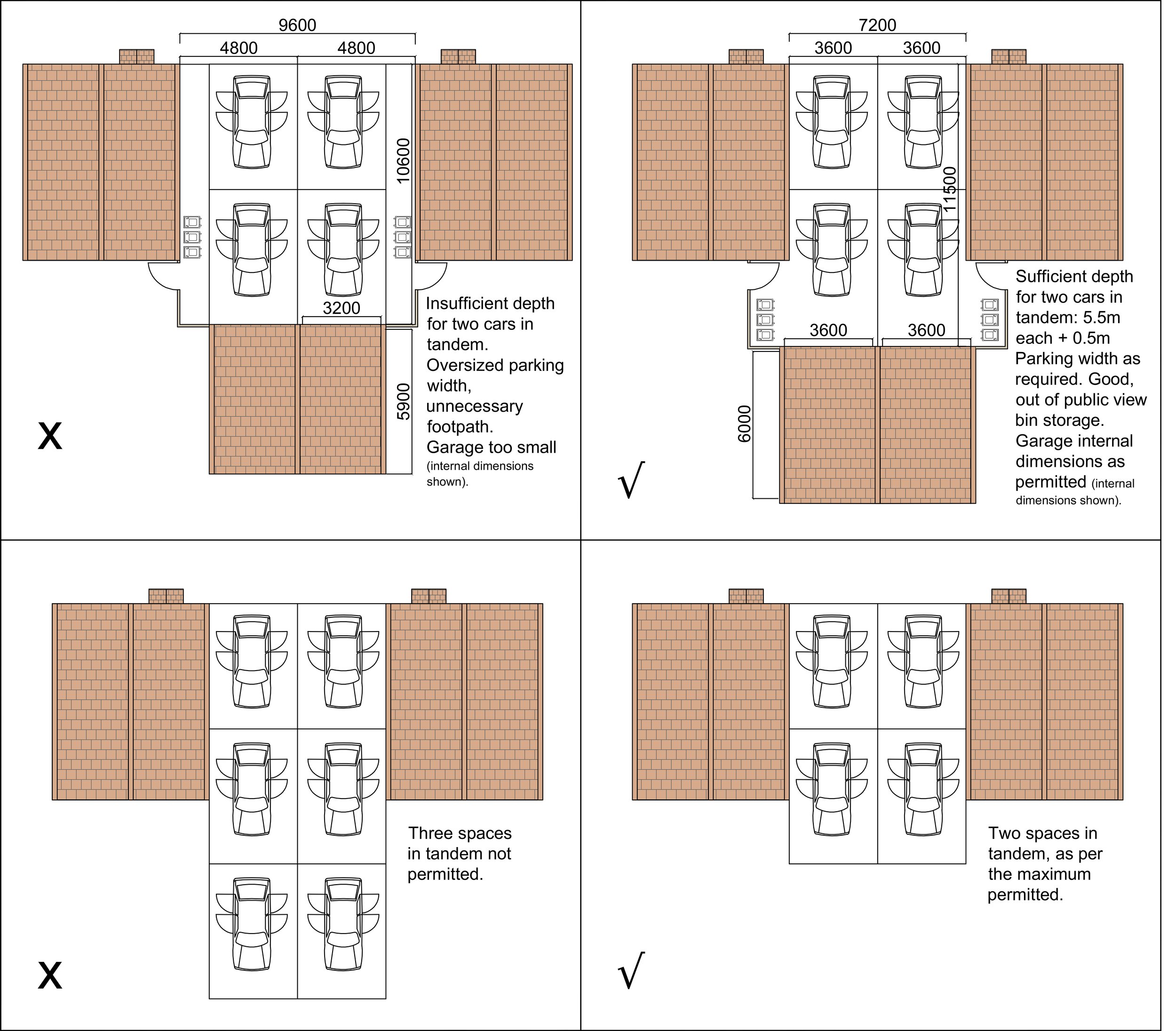

It appears that the design of on-plot parking is not fully understood. Applications often include small niche-parking spaces appearing within garden fence enclosures located at the end of rear garden boundaries. Not only this arrangement is highly inconvenient for residents, but often the parking widths do not permit car doors opening, or parking arrangements include cars parked in tandem without enough width to walk around cars, clearly an impossible parking situation.

6. Driveway Parking

There is a clear lack of rigour and consistency in the provision of driveway parking. Proposals ranged vastly in width and length, in most cases being oversized but at times being so narrow cars would not be able to open the doors whilst parked on their own driveway, or having three cars in tandem on spaces without space to walk around the vehicles. Overall, there were significant amounts of land wasted on driveways, particularly when layouts showed curved streets.