How we work in Nottingham ...

A long process put Nottingham at a national leading role in securing quality of design through the planning process. Over a decade ago, Nottingham embraced the concept of Design Champions to raise the quality of schemes. Les Sparkes was the chair of the City’s independent Design Review Panel and briefly became an external Design Champion for Nottingham. Although the use of Design Champions was short lived, the decision to take that route gradually drove Nottingham towards a different approach, a much more complex but stable design quality system that developed organically and eventually became part of the culture of the City Council.

A change of culture requires political stability ...

A few years back, surveys showed that the quality of design in the built environment was in decay and so it became a key priority across the UK. A regional CABE review of building (2006) quality showed that 42% of homes were substandard, which correlated with the quality of places being built in Nottingham. In Nottingham, the Heritage and Urban Design Team took the lead on this issue at the City Council. The use of an independent Design Champion initially seemed like a good idea but in time, it became apparent that it was inadequate as an instrument to promote design quality. There are two significant issues with the concept of Design Champions that are difficult to reconcile with collaborative, collective approaches to Placemaking: despite the level of expertise, a designated professional was unlikely to have an opinion on design that was entirely objective; and there was a risk that this opinion would seem to be superior to everyone else’s views. Appointing Champions had a perceived danger of making built environment decisions an elitist process and the quality of place an issue concerning the academically adept over others. Instead, a system where the role of leading professionals was equal and level with all other stakeholders with investment and interest in place, seemed like an option more likely to foster a culture of pride, ownership and place-care. The problem with this democratic approach was that, to achieve collaborative Placemaking in practice, two significant changes were necessary: a change in culture so that everybody understood technical concepts and could communicate what good design meant to them; and a review of the planning processes so that tools and strategies could support the change. On the face of this dilemma, 15 years ago, the City embarked on a long-term plan to forge a culture where place quality was at the heart of every project, no matter how big or small.

The epicentre of this change was the Heritage and Urban Design Team. Initially, staff found significant barriers to promoting place quality: there was a perception that quality costed more, and the various gains were not quantifiable; the value of good design had not been evidenced sufficiently to justify some political decisions. However, as time passed, where minor risks could be taken, projects became roaring successes. Public realm improvements like the Old Market Square were soon loved by all and are still celebrated. Gradually, in-house experts gained the trust of leaders and politicians. Together, technical staff and decision takers found a way to communicate effectively and work well as a team. A significant factor that allowed this process to take place was the political stability in Nottingham, where changes were not radical enough to jeopardise the gradual development of this working ethos. Strong, stable, long-term leadership meant that perceived risks could be taken and perhaps more importantly, trust was built over time.

Promoting a good working ethos ...

Councillors and key decision makers began to appreciate the value and benefits of good design and collaboration and a goal was set for staff to work together across departments in a collaboratively way. Different teams began to understand each other’s technical language and come up with formulae that worked for all. Staff across teams established shared processes that were timely and avoided delays. These are now being incorporated in various guides to offer applicants more clarity and certainty regarding the steps towards achieving planning approval. The process of producing these has proven to be more important than the documents themselves: bringing all parties together in a collaborative environment is invaluable to achieving consensual good quality design advice. Crucially, the Heritage and Urban Design Team began to become involved in every pre-application and planning submission appraisal, working alongside the Planning team in a positive, collaboratively way. Building for Life was adopted by the Council, the Geographic Information System (GIS) team developed the 3D city massing tool to work alongside urban designers and the independent Design Review Panel was used more often to appraise schemes. Nottingham soon became an avid user of the pre-application process and currently, schemes are developed by practitioners in collaboration with an in-house team of experts. The changes also involved the introduction of the Design Issues process, a weekly meeting of officers where all departments involved in a scheme sit together at various stages of the pre-application or planning process to review design quality. Formal appraisals, including a multidisciplinary commentary, are produced for applicants after the meeting. This process not only facilitates conversations and helps all officers involved in the development process to overcome design constraints by arriving to consensual solutions, but it also brings everyone up to speed with the main concerns and goals of the various expert fields and departments. Notably, a strength of the City ethos is the confidence of accepting that not everything can always go to plan and that some design solutions and on-site management do not deliver expected outcomes. Staff and leaders regularly review schemes to appraise positive and negative aspects of the design and the process. These evaluations become a tool for training and form a case study archive that is regularly used as a reference to inform other schemes.

Offering certainty to investors ...

Inward investors want certainty and a good degree of confidence within the City. Nottingham is achieving this through comprehensive spatial strategies such as the Heritage Strategy, and the City Centre Urban Design Guide (2009). A programme of strategic master plans is currently being produced for the City Centre as well as Supplementary Planning Documents for regeneration zones and large sites. These detailed frameworks, developed in-house, have offered some confidence and certainty to commercial investors and have been crucial to support bids for additional funding. For example, the Heritage Strategy was pivotal to Nottingham winning bids through the Heritage Lottery Fund and the biggest Heritage Action Zone allocation in the country. It was through this funding that Nottingham finally opened its Urban Room in 2018, after years of detailed planning following the Farrell Review (2013). Planning delivery funding from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government helped the delivery of this Design Quality Framework (DQF). The framework involved an in-depth analysis of gaps and downfalls in the quality of places and buildings built in Nottingham, and in the planning processes that led to them. The study also highlighted positive approaches. For example, it evidenced the value of the pre-application process as a tool to speed up the planning process and to reduce the number of planning conditions. It also evidenced the need for adopting the Nationally Described Space Standards through the Local Plan, supported by the inspector of the examination. The results of this analysis informed the production of a series of design guides developed in collaboration with industry, residents and local communities. The impact of the DQF process itself is perhaps equally important, as it has fostered a positive change in the way in which the Council works with local communities and the public. Four of the DQF documents when launched in April 2019: The Introduction to the DQF, the Housing Design Guide, The New Streets Design Guide (developed in collaboration with PJA) and the Facades Design Guide, other documents followed within 12 months.

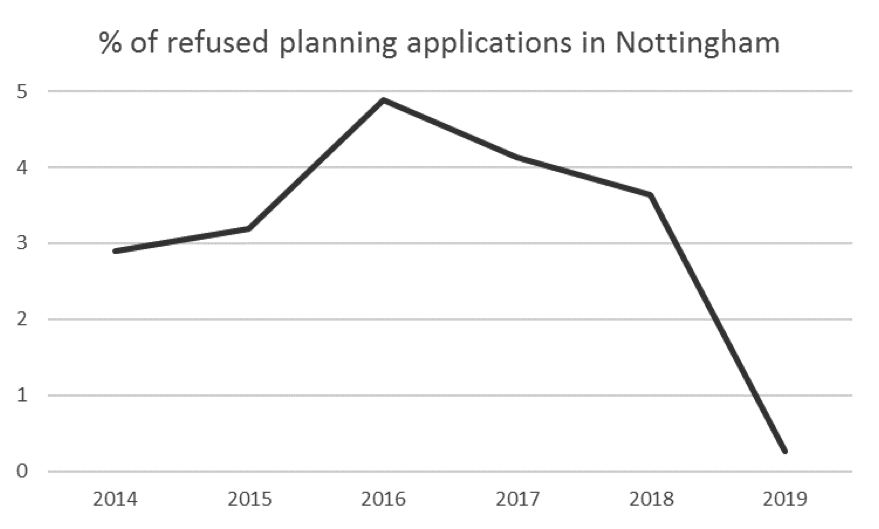

Another strategy introduced by the Council was a Pre-Agenda meeting, an informal gathering where technical staff and decision takers discuss the forthcoming items of the planning agenda, informally but in detail. This gives councillors the opportunity to understand constraints and the reasoning behind some design solutions prior to planning committee. Through this procedure, planning committee members are made aware of the changes that have often resulted from extensive negotiation. It is another way of making councillors aware of the design process and its nuances, and building that all-important trust. As councillors have made the commitment to become involved in the pre-application process and work together with technical staff, the number of planning refusals is now extremely low, which gives confidence to applicants that working in collaboration with the Council, listening and taking comments on board, can speed up the process and remove barriers to achieving planning permission. The figure below shows how the percentage of refused planning applications changed over time, initially increasing when quality of design became more relevant, and decreasing rapidly once that change in culture was more widely embraced.

Politicians have become gradually more involved in design quality conversations and are now part of the movement striving for better design. Over time, they developed a taste for good design and an urge to understand technical issues and use of a common language. The City has now programmed Urban Design and Place-making training for Councillors and committee members. Workshops will involve the review of those schemes where leaders and staff have been involved, and will include desktop studies, site visits and the use of appraisal tools such as Building for Life and Nottingham Design Quality Framework tool kits. The question is currently how to ensure the process also engages Nottingham citizens.

Percentage of refused planning applications in Nottingham between 2013 and 2019.

Investing in Urban Design ...

Contrary to the national trends, the City Council has expanded the Heritage and Urban Design Team recognising the value of ‘place quality’ as a vital part of the city’s future. This decision has meant that, with adequate software and a strengthened team in-house, the Council’s expertise in heritage, archaeology, conservation, funding sourcing, history, urban design, architecture, illustration and social sustainability, the value of good design became the driver of a significant business model that could help Nottingham make the most of its assets and secure long-term financial sustainability. To that end, it now offers its skills to external partners in helping design buildings and housing layouts.

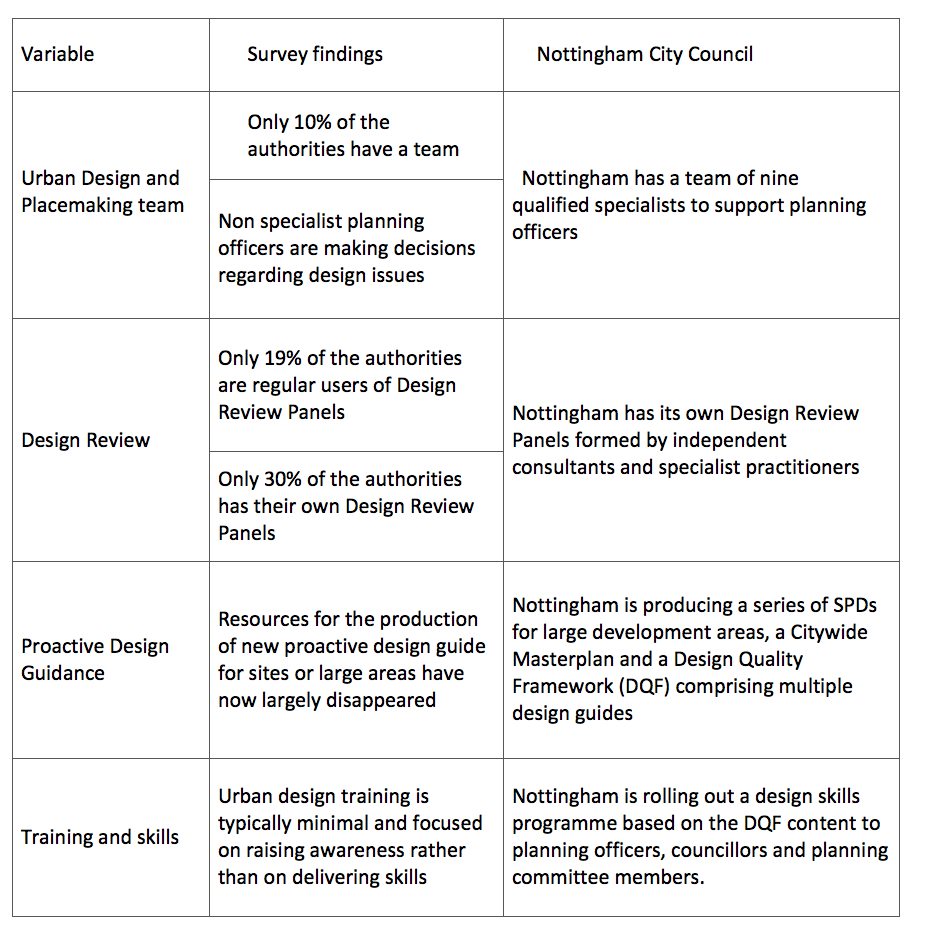

In 2017, the Urban Design Group and the Place Alliance conducted a survey of Design Skills in English Local Authorities and Nottingham City Council took part in this survey. The survey measured 4 key themes: Change over time; In-house capacity; Design review; Design guidance and training. The table below shows the average results of the study in comparison to Nottingham City Council’s service.

Watch update on Design Deficit in Local Authorities 2021 clicking here.

What happens next? ...

The investment in Urban Design skills brought significant positive changes in Nottingham. The City Council will continue to evolve this model of strategic planning, attention to detail, collaborative work and continuous learning.

Councillors in Nottingham are aware that as we move towards an age of placemaking, the planning process needs to adopt tools and strategies that will enable multidisciplinary teams to work closely together and needs to have communities and residents’ input at their heart. They understand their role in place leadership and so the next stage of Nottingham’s development involves making the planning process more open and available to the public to implement and establish inclusive, accessible placemaking tools that enable everyone to have an equal voice and an opportunity to shape their city. The Urban Room project and the development of the DQF with an inclusive ethos are testaments to this commitment.

Nottingham City Council welcomes other local and regional authorities interested in our model or tools, those seeking support or advice, or those willing to share their expertise to get in touch.